I’ll admit that I hold my children’s teachers to a higher than reasonable standard. Would you want my kid in your English class? As a parent, I could be a burr in your saddle. I get that.

I’m not a harassing parent, I promise. Most of my children’s teachers have no idea who I am, other than Celeste and Sarah’s mom. That’s how it should be.

On the other hand, my children’s teachers don’t know who Penny Kittle is. They don’t know who Kristin Ziemke is. They don’t know who Kelly Gallagher is.

Heck, my children’s teachers don’t know who Nancie Atwell and Lucy Calkins are. It doesn’t matter if they’ve read my books about teaching reading, but it does matter when my children’s teachers haven’t read a book or article about teaching reading in 20 years.

A line divides parents who know a lot about reading and their children’s less-knowledgeable teachers. What can we teacher-parents do when our children have poor reading instruction at school? I may not have my own classroom this year, but this reading war front line cuts across my lawn. It stretches across my dining room table—limiting and defining my children’s reading lives.

My oldest granddaughter, Emma, spends an hour and a half at our house every morning and afternoon. My husband walks Emma to first grade. We help her with homework. Celeste, my older daughter, joked with us last week, “Andrew and I don’t think we’re are going to have to worry about Emma’s reading log all year. It’s always filled out when we pick her up.”

Of course, I’m going to read with her. You can bet your tail feathers that I will monitor my grand baby’s reading homework.

Emma has a reading log. Each day, she’s supposed to read for 20 minutes. We record the book titles for what she reads and sign Emma’s log. Kids with unsigned reading logs receive consequences at school. Emma’s vague on what happens because her log is always signed.

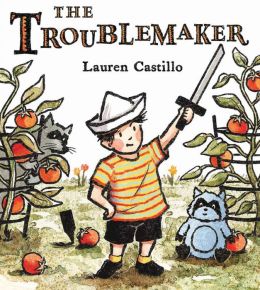

Last week, Emma and I re-read three outstanding wordless picture books, Flashlight by Lizi Boyd, The Troublemaker by Lauren Castillo, and Molly Idle’s Flora and the Flamingo, a 2014 Caldecott Honor Book. Filling out her reading log, Emma said, “We can’t write those books down, Mimi. We didn’t read any words.”

Last week, Emma and I re-read three outstanding wordless picture books, Flashlight by Lizi Boyd, The Troublemaker by Lauren Castillo, and Molly Idle’s Flora and the Flamingo, a 2014 Caldecott Honor Book. Filling out her reading log, Emma said, “We can’t write those books down, Mimi. We didn’t read any words.”

These books are standouts—amazing pieces of storytelling. Award-deserving. Emma recommends them, too.

Sadly, they’re not reading log worthy.

Somewhere in Texas, on a first grade teacher’s desk, sits a reading log with my signature on it. I have publicly denounced reading logs for a decade, but I still sign one every night for my granddaughter. I feel the injustice every time I hold the pen.

And the world spins madly on.

Our younger daughter, Sarah, is a high school sophomore this year. Sarah is a reader. Well, Sarah was a reader. Her dad and I hope she will be a reader in the future. She doesn’t read much any more. Burdened with pointless assignments for English class, Sarah doesn’t have time to read or write at home. Her English teacher doesn’t give Sarah and her classmates time to read or write at school, either.

Sarah is in the gifted and talented program. She’s an International Baccalaureate student. She takes an advanced English course. Sarah’s first project this year? Make a collage about The Beast from The Lord of the Flies. Her second project? On the corners of a tissue box, share your hopes, dreams, fears, and personal creed. I guess Sarah’s teacher needed Kleenex.

Sarah told us that the kids didn’t even share their boxes with each other. They just stacked their boxes on a table. That’s where kids’ hopes and dreams belong—in the back of the room.

Two weeks into school, and Sarah still hasn’t read a book or visited the school library with her class. The Lord of the Flies was assigned for summer reading.

Last week, Sarah’s teacher launched a discussion about “why reading matters” and “what makes a book worthy.” She lectured the class for an hour about literary merit. She never asked students to contribute their opinions about the importance of reading and the value of books. What could Sarah and her classmates possibly know about reading? She’s the teacher. She knows why reading matters.

It’s clear that my children’s teachers value school-based definitions of reading. Reading matters outside of school, too. I’m glad Emma and Sarah learned this at home, but what about the kids who don’t?

On Facebook this weekend, I invited friends to share the worst reading assignments they’ve seen as students, parents, and teachers. In many cases, our children complete the same boring, teacher-directed reading assignments we did 30 years ago. Putting low-level comprehension questions on iPads doesn’t improve the questions.

My Facebook query opened a floodgate. Dioramas, book reports, paragraph and chapter summaries, Accelerated Reader quizzes—teachers confessed to assigning landslides of pointless busy work to their students. Parents bemoaned burdensome reading logs and worksheets. Librarians complained about teachers’ restrictive book selection criteria that prevent children from self-selecting books—unreasonable page limits, reading level boundaries, and narrow genre requirements.

What are children really learning from us about reading?

I’m not a perfect teacher. I’ve assigned some crummy, waste-of-time, language arts and crafts projects to my students over the years. Cereal Box Biographies, novel unit packets, and vocabulary crossword puzzles—my students churned out a lot of mindless work. It finally occurred to me that if I hated grading 98 cereal boxes, my students hated making them.

I’m still learning how to be a better teacher. I’ve missed a lot of chances to connect my students with reading. I’ve created negative reading experiences in my classroom. I didn’t know what I know now. I learned. I grew. I evolved. I improved. I was a novice teacher once, but I’m not new any more. When you know better, you do better. No excuses.

Celebrating Dr. Seuss’s birthday on March 2nd can’t offset a year of reading logs and book reports. Our children must spend more time reading than they spend completing reading-related activities. Generating grades shouldn’t drive teaching decisions. Our children must develop positive reading identities. Worksheets don’t value readers or reading. Children should not become readers in spite of school.

At some point, ignorance becomes a choice. When teachers reject evidence-based teaching practices in favor of outdated traditions, it’s a choice. When parents endure the disrespectful, useless reading work our children bring home, it’s a choice.

Share what you know. Learn as much as you can. Build relationships. When we remain silent—afraid to rock the boat, offend a teacher, or question an administrator, it’s a choice. What choices do our children have?

We must advocate for children’s reading lives, or they won’t have reading lives.

If we don’t speak up, too many children will make the only reading choice they have left. They will choose not to read.

*** Note added on September 14, 2014.**

The response to this post has been overwhelming. While most of the comments I have received in person, through Twitter and Facebook, and here on the blog have been positive, a few have been hateful and derisive–including curse words, cruel remarks about my children, and personal attacks–which I have chosen not to approve on the blog or respond to elsewhere. I cannot possibly restate everything that I have written and spoken over the years about meaningful reading instruction in a single blog post. I cannot summarize decades of reading research, either. What I can do is respond to specific questions or remarks.

Yes, I know that reading wordless books doesn’t provide my granddaughter the same skill development that decoding words does. What wordless books offer is practice generating stories by inferring visual cues from the illustrations. This is higher-level thinking–valuable for young readers to practice.

It bothers me that my granddaughter is learning in first grade that some types of reading “count” and some don’t.

Reading logs do not hold children and parents accountable for reading home. Reading logs hold children and parents accountable for filling out reading logs.

I am not against the arts. I am not against artistic expression in language arts class. I believe that inviting children to choose how they want to respond to a text is better than assigning the same project to everyone. Students should spend the majority of language arts class reading, writing, and discussing reading and writing. I believe writing is art and reading is art appreciation. We must be critical of activities that crowd the Ianguage arts out of language arts classes.

I do not think I am better than other teachers. I admit in this post that I have made mistakes and continue to learn. Reading professional books and articles, attending conferences, joining Twitter chats. attending PLC meetings, talking with colleagues, enrolling in courses–I invest substantial time learning from OTHER teachers. I am grateful for the vast learning community of colleagues who teach me every day. Like many of you, I know that being a good teacher demands investment in my personal learning.

I appreciate the many parents and professional colleagues who have engaged in meaningful discourse about this post over the past week. I look forward to learning more from you.

After reading this post, there were many aspects that resonated with me. First, is that many students aren’t always given the opportunity to learn to love reading. This was the same for me growing up. Everything I was asked to read for school was an assignment. Never once was I allowed to pick something out that I was interested in to meet the requirements of an assignment. I developed a love of reading on my own (and with the help of the adults around me). Only a handful of times can I say that the books I read for a classroom assignment really were ones I enjoyed (Lord of the Flies, To Kill a Mockingbird, Ender’s Game), and/or lead me to finding similar books by that author.

I loved when you described your own imperfections as a teacher. I think this is really brave! Many people think what they have been doing for a long time will always work. They refuse to evolve and grow with the students each year. It is very frustrating (especially from the standpoint of a support teacher who wants to be in the classroom). I love to learn and grow, so it is nice to see teachers who have a wealth of knowledge admit they don’t know it all and desire continued professional development.

One truly powerful statement (for me) from your post was, “…some types of reading “count” and some don’t.” All types of reading are important. The idea of literacy is constantly changing and, like our students, we all need to explore and adapt to new ideas and understandings. We need to take time to develop the whole child and allow them to explore different genres of text. Students will develop skills of all kinds if they are put in situations where books (and time to read them) are plentiful.

I am looking forward to continuing to read your books!

I want to leave this blog post anonymously on a few colleagues’ desks! We have been lucky enough to have amazing instructional coaches who lead us in best literacy practices. The number one rule I’ve learned is that in order to learn how to read and grow as a reader, a child must READ! We need to provide students the choice in what they read and the time to engage in reading. It is incredibly frustrating to see educators continue to teach skills in isolation rather than in authentic texts. Being a leader in literacy, how do you address the lack of actual reading with resistant teachers?

Thanks for writing one of the bravest educational posts I have ever read. Schmoker’s Crayola Curriulcum was my previous favorite. This is now my number one. With your permission, I’d love to reblog on my site http://www.simplyinspiredteaching.com

Kari Yates

I agree with you and the mundane tasks we ask students to do for the sake of work or “reading.” I ran across your blog because I am looking for meaningful ways for students to share what they have read. I think book talks are one way that is a real world application, but I was looking for a variety of ideas to meet the different needs in a classroom. Any ideas?

Read “The Book Whisperer” and “Reading in the Wild,” both by Donalyn

Donalyn, first thank you for being so open and honest about your growth as a reading teacher and the “mindless work” your students have participated in over the years. All teachers are on this path of learning and hearing that you yourself have had some human “teacher” moments is uplifting.

I am a young teacher and have only been in the classroom for three years. The “right” way to teach reading has changed every single year in my district. I really connected with what you said about being advocates for our students as readers. “Rocking the boat” as you put it, is sometimes hard for new teachers. I am not tenured, I have little experience, but I do have knowledge to share as I am completing my Masters in Literacy and learning so much.

You stated that your kid’s teachers didn’t know the leading voices in literacy. I felt empowered when I read those names and knew most of them and what their philosophies are on reading. As teachers, how do we expect to teach our students in the ever-changing world if we don’t learn and change ourselves? Your post has made me want to share my new knowledge with my colleagues and stand up for my students. The love for reading is so important, more important than a worksheet or project. Thank you for your words!

Thank you very much for sharing! One of the things that I feel inspire my 4th grade students to read and love reading is modeling through fabulous read-alouds. When we read aloud, even to older students, wonderful things happen. Our discussions are in-depth, and students notice more than the summary of events, but also figurative language, juicy vocabulary, theme… When they really enjoy an author, they begin to “borrow” elements to use in their own writing. Also, literature circle groups have choice in what works they will read, and their discussions have emulated our read-aloud discussions. Some people I work with feel that we don’t have the time for read-alouds, but it’s been so powerful in my classroom. It’s so exciting!

So important! Don’t lose faith, DM! There are still teachers who strive for deeper thinking.

i learned to read sitting or laying down next to my mom and reading a book we had bought together. She would buy hers and I got to choose mine. Oh, those are the greatest childhood memories. Through my years as a reading teacher, it had always bothered me that my students had to complete assignments instead of reading. Then, you appeared in my life!!! Thank you for comfirming what I’ve always knew. Now I got to quote you every time administrators look at me weird because my students read in my reading class. Thank you thank you!!

I completely agree with you. Reading is not and should never be considered a “school” activity. Reading is a lot lifelong learning experience. It should engage, teach, and provide new and exciting experiences for a reader. I believe as teachers we should expose students to multiple genres and let them decide what they enjoy and/or want to learn more about. I don’t believe in reading logs either. How many times do parents just sign them because they are expected to? It doesn’t matter if a book was actually read or discussed. Reading should be an exploratory event. Only then can we help our students truly read.