While educators, families and kids walk into every new school year refreshed and hopeful, we are all exhausted and brain-fried by the last month of school. We push more and more things into our “I will get back to this when summer starts” pile. For many of us, our summer piles are stuffed with books we plan to read when we have more time.

It’s natural for reading to fall lower on our list of priorities now and then. We can fill our days with a hundred activities that aren’t reading. For every night we spend binge reading a book until the wee morning hours, we can point to weeks when we didn’t read anything more than Facebook posts. It happens to every reader.Our reading lives ebb and flow. Summer’s slower pace gives us breathing room—an opportunity to recommit ourselves to daily reading.

I started the #bookaday challenge in 2009 because I realized that my family and I read less during the last six weeks of the school year than any other time. Overwhelmed by end-of-year projects and school celebrations like band concerts and award ceremonies, we let our nightly reading routines slip by the wayside. When we did talk about reading, we talked about what we wanted to read during the summer.

Announcing the first annual Book-a-Day Challenge was a public declaration of my commitment to read one a book a day for every day of summer break. In the weeks leading up to summer vacation, I talked with my students continuously about how fun and exciting it would be to read as much as they wanted over the summer. We made lists of books they might read. I loaned books out for the summer. If I believed what I told my students, I needed to read more and ensure that my family read more, too. Beyond my responsibility as a reading role model for the children in my life, I needed a challenge. I wanted to kick start my reading life and push myself to read more than I ever had.

I read 75 or so books that summer and rediscovered my reading mojo. My summer memories included wonderful reading experiences—languid days spent reading under my ceiling fan, taking my children to the public library and checking out a Radio Flyer wagon full of books, and connecting to the burgeoning online world of book lovers and educators. Beyond the personal benefits of Book-a-Day, the challenge reinforced the power of book talking to connect my students with engaging books. I walked into my classroom that fall with two overflowing bags of books to promote and share with my new students.

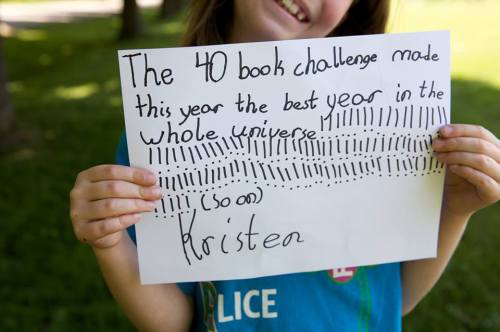

Over the past seven summers, Book-a-Day has grown and changed. In 2010, Book-a-Day became #bookaday and participants began using the hashtag to connect and share books on Twitter. In 2011, I met Colby Sharp online during the #bookaday challenge. The Nerdy Book Club community grew from the conversations #bookaday participants were having online every day. Folks started shorter #bookaday challenges during winter and spring holiday breaks. Jillian Heise created the picture #bookaday challenge, pledging to read one picture book with her middle school students for every day of the school year. Teri Lesesne and I shared the origins and benefits of the #bookaday challenge with colleagues at the Texas Library Association conference last month and invited everyone to join. More than a summer reading challenge now, the #bookaday community continues to share books and celebrate reading all year.

Colby Sharp’s first #bookaday tweets in 2011.

The summer #bookaday event endures as an annual opportunity to hit the reset button on our reading lives, connect with other readers, celebrate books, and remind ourselves how much reading matters to our lives and the young people we serve. If you have participated in past years, welcome back! If you are new to the #bookaday challenge, don’t be intimidated!

It doesn’t matter if you actually read a book every day or not. Dedicate more time to read. Celebrate your right to read what you want. Make reading plans. Share and collect book recommendations. Connect with other readers.The #bookaday challenge is personal, not a competition. Finish that series. Tackle that epic historical your mother gave you for your birthday (last September). Try audiobooks. How would you like to grow as a reader this summer?

The #bookaday guidelines are simple:

- You set your own start date and end date.

- Read one book per day for each day of summer vacation. This is an average, so if you read three books in one day and none the next two, it still counts.

- Any book qualifies including picture books, nonfiction, professional books, audio books, graphic novels, poetry anthologies, or fiction—children’s, youth, or adult titles.

- Keep a list of the books you read and share them often via a social networking site like goodreads or Twitter (post using the #bookaday hashtag), a blog, or Facebook page. You do not have to post reviews, but you can if you wish. Titles will do.

Since I work year round now, I never really stop my #bookaday challenge. I read on average a book a day all year. Some days, I read twenty picture books. Other times, I spend a week or more savoring a lush book. The measure of a reading life isn’t how many books we read. It’s the experiences, the knowledge gained, the connections we make with other readers that make our reading lives meaningful. The summer #bookaday challenge gives us the chance to remember what we love about reading.

I am planning a wonderful summer of travel—inside and outside of my books. I hope our paths cross during the Eighth Annual #bookaday challenge or during my summer road trips. I look forward to connecting and sharing with you.